Time out for a little fun that came my way the other day when I was contacted by a man named Wesley Miller. Mr. Miller has an interesting collection of animation art: it consists of cels or drawings of characters being hit over the head. He had contacted me becuase of an episode of the sitcom King of Queens I worked on in which the main character goes to bed in a fever, leaving the television on; he keeps changing channels, and in his delirium sees himself and his family in various popular TV shows (Wheel of Fortiune, The Honeymooners), one of which is animated. In each segment his deceptions are discovered by his wife, and in our animated piece she hits him over the head with a mallet, then a skillet, and finally a piano.

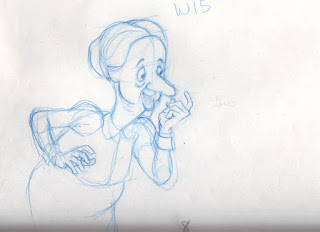

When I replied, he sent me a scan of one of his acquisitions, telling me only that it was a Disney cel. Here it is:

I decided it would be fun to see how much I could deduce from the image, based on my own knowledge of the evolution of Disney styles and practices.

First of all, the characters were unknown to me--probably one-offs that did not appear in any other cartoons. Most likely, it was from a Silly Symphony.

Notice the peg holes at the bottom: there are 5 of them. This confirmed that it was Disney, all right, as the system is similar to Acme punching in that the end holes are oblongs and the center hole round. The second and forth holes are uniquely Disney: a system for archiving the cels in binders; in this way the binder rings do not deteriorate the registration holes. However, at Disney the old registration system of just two round holes was used into the early 1930's, so this cel must have come from a production that came after that innovation.

My next clue was more subtle: the drawiing style. There is a crudeness and casualness to the drawing that, to me, places this example in the early thirties. By 1936 the whole studio had been transformed by drawing classes and by high-minded work on

Snow White into a temple of deliberately stylish drawing, often influenced by anatomical knowledge even in the case of the most cartoony characters. The famous

Three Little Pigs of 1933, despite its fine animation and characterization, still contains much design of the old school of animation: circles for heads and bodies and some rubber-hose style limbs. Notice in the cel, how the judge's hands are inconsistent in their rendering: on the right hand, the little finger is longer than the ring finger, and the thumb seems to be confused with what may be a button on his robe. A year later, no such ambiguity would be permitted at Disney. The left hand with the mallet is equally casual with its small thumb and uncertain grip on the handle of the mallet, the head of which is squashed unconvincingly.

Even though this scene may have been the work of a junior animator, by the late thirties the styling even of inbetweens was rigidly consistent throughout the studio.

So I told Mr. Miller that I thought his cel was from between 1934 and 1936, and most likely 1934. And it was! Turns out it is from the Silly Symphony

Who Killed Cock Robin?, which is most famous for its Jenny Wren character, a marvelous caricature in styling and movement of the voluptuous actress Mae West. Released in 1935, it was probably drawn in 1934.

On YouTube, with a little work, I managed to isolate the very frame of film that captures this cel. Here it is:

Notice that the expanding white impact flash now stands out well against the painted background. The blur lines that trail after the mallet, however, hardly can be seen.

If you would like to see the whole cartoon,

here is a good link.

This cartoon is a good example of the old style being overtaken by the new. Let's look at a few more examples of this.

![]() |

| The repeatable gag, not repeated. |

In the silent and black and white cartoons, well into the thirties, a funny gag was repeated once, twice, even three times, in an effort to get more mileage and screen time out of the footage. This may have also been in the belief that the audience liked the repitition, or didn't realize they were seeing the same thing over again, or was too stupid to appreciate it in just one viewing. In the beginning, Disney cartoons were as guilty of this as Warner Bros or the Fleischers. At any rate it was commonplace, and here was a gag with that potential: the ambulance is flying along, encounters a big tree, and must veer sharply to make it between the bows. But to my amazement, they do it only once! The Disney studio has learned some restraint.

![]() |

| The cloned character gimmick. |

Here's another convention that goes way back at all the studios, another technique regarded as a saver of time and work: animating a character once, then inking the drawings multiple times, each time with the image displaced on the screen so that there appear to be two or more characters--in this case, eight!--all moving in unison like Rockettes. Ub Iwerks did it in

The Skeleton Dance from 1929, and it even appears as late as 1976 in Richard Williams feature

Raggedy Ann and Andy (some dancing dolls).

But again, times were a-changin'...

![]() |

| Seven cops, seven different movements. |

|

|

In another scene, these Keystone Kops characters, while all exactly alike in design, are all moving independently. Disney has learned the appeal of complex and diverse movement in their quest for the "illusion of life."

![]() |

| The stereotype of the simple and lazy black man. |

Racial stereotypes are found in many cartoons of this period, and even way into the 50's (how about the lazy Mexicans in Friz Freleng's Speedy Gonzalez cartoons?) and the Disney organization was no exception to the rule. Here we have a slow-talking character in the mold of Stepin Fetchit, dressed as a sleeping car porter, being victimized by a cop with an Irish (!) accent.

![]() |

| The tough guy raises his belly up... |

![]() |

| ...then lets it drop in a gesture signifying the bravado of a bully. |

|

Here's a peculiar old gag that goes back at least as far as Pegleg Pete in

Steamboat Willie. I may be wrong, but I think it is exclusively a Disney gesture. It may be just a takeoff on someone ostentatiously hitching up his pants.

![]() |

| Pete in Steamboat Willie, 1928, before he got his peg leg. |

Here's Pete at full lift before dropping his belly, seven years prior to to the character in

Cock Robin. Old gags die hard.

![]() |

| Mae West aka Jenny Wren. |

And here is an image of the Jenny Wren character, a real tour-de-force of personality animation for its day .

Please let me know if you enjoy this kind of analysis of some of the old Hollywood animation. If I get a good response, I will do more.