Whenever I take on a new software application, there is of course a period of intense struggle, the learning wall that I must climb before the program can be any fun to work with. This is inevitable, and I have come to expect it.

In the case of Toon Boom's StoryBoard Pro, the wall was a short one, and I was boosted over by my previous experience with Toon Boom's other applications: first Studio, beginning back in 2006, then Animate and, finally, Animate Pro 2. This was helpful because of the great similarities in the UI and terminology among the various ToonBoom applications, so that even as I opened the storyboarding program for the first time, much of what I saw in front of me was familiar--the same tools, icons, and organizational structure that I already knew.

Furthermore, Toon Boom's unparalleled tutorial resources which they provide free for all their applications, plus other tutorials both amateur and professional on You Tube, help to answer the many questions that arise when attempting to master StoryBoard Pro or any of their other products. Why all other software companies do not make similar efforts to freely educate the public in the use of their applications, preferring to rely on pay tutorial services, I do not understand. The more people there are who know how to confidently use your product, the more likely it is that it will be bought and used. Toon Boom has certainly got the right idea here.

The big attraction for me to StoryBoard Pro was its capability to generate animatics complete with camera maneuvers and soundtracks.

The big challenge for me, I knew, was to learn to comfortably draw directly into the panels with my stylus and Wacom tablet.

Working With a Script

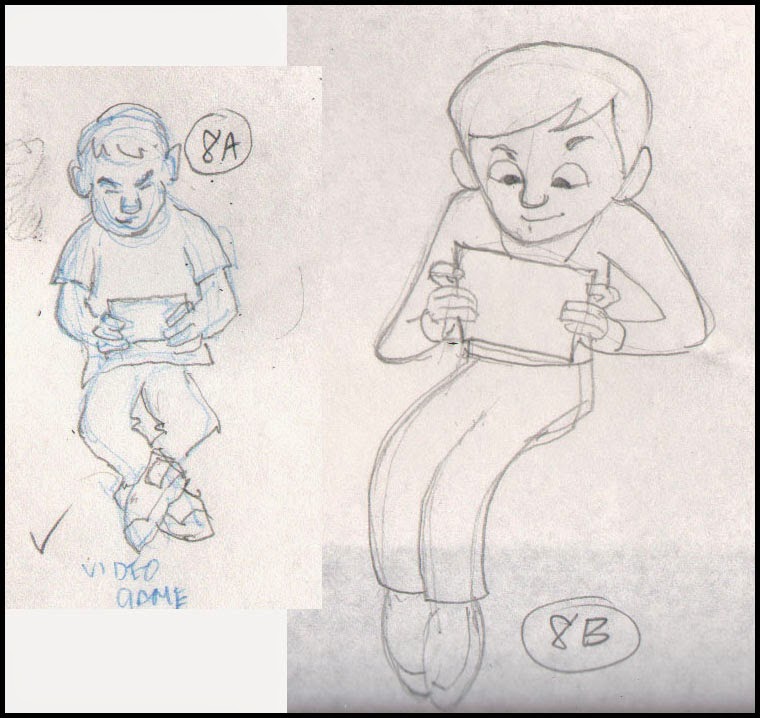

Using as my test project the concept I call

The Two Washingtons, the same one for which I have recently recounted my character design process [

Acme Punched! posts no's 64 and 65], I started by writing a script complete with dialog and camera directions, during the course of which one of the two main characters changed completely in concept and had to be re-designed (see below.)

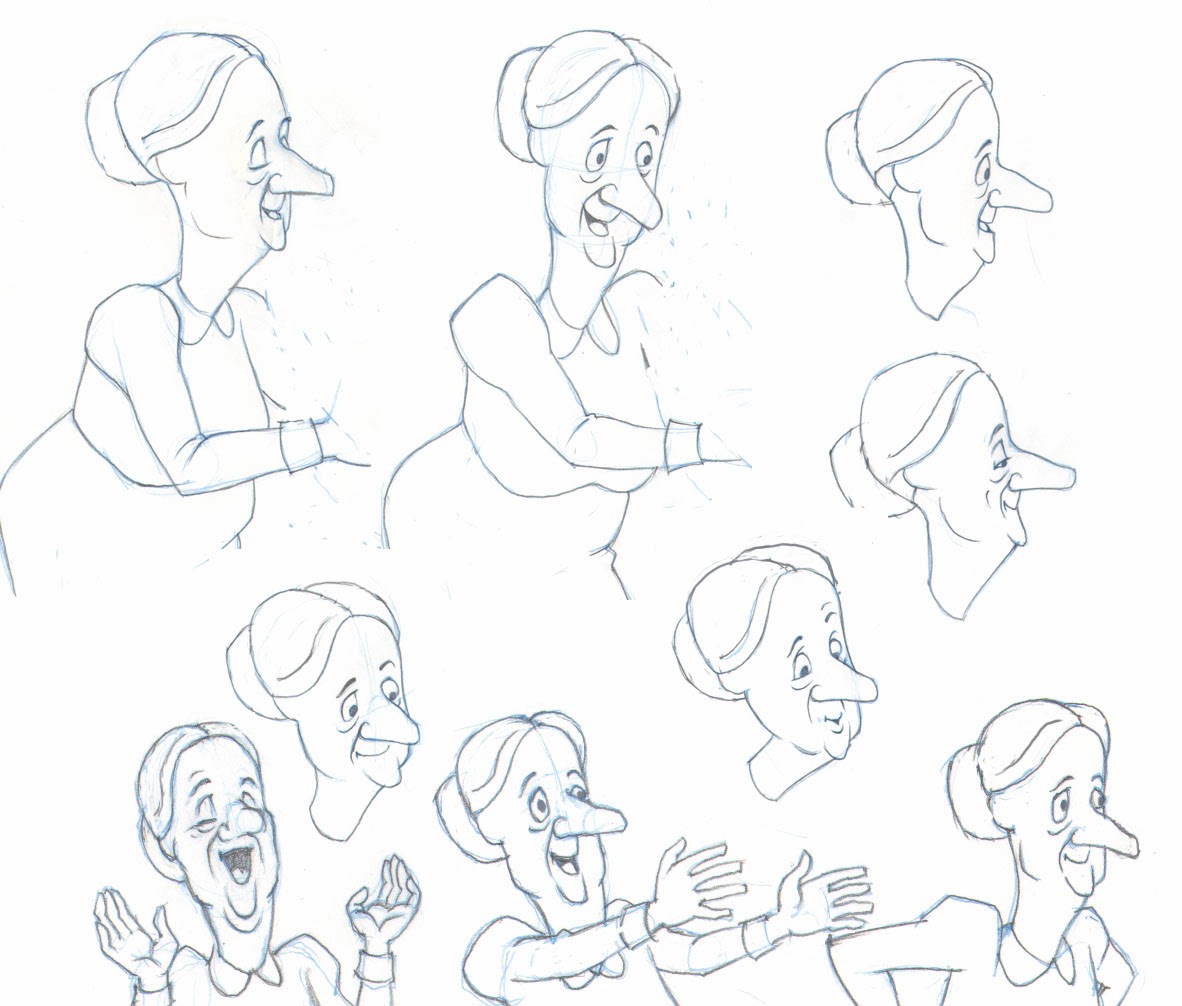

![]() |

| A change in character often necessitates a change in design. |

The script notations included a sequential number for every

scene (or camera

shot, as it is called in live action.) My script had 24 scenes, so when I opened StoryBoard Pro for my new project, I laid out 24 scenes and copy-pasted the directions for each scene from the script into the Action Notes box in the Panel View. (I should note that as I write this, some of the staging for what is now scene 24 is unclear in my mind, and so I expect that when I get to that point in my storyboard, it will end up being divided into several more scenes. But the flexibility of StoryBoard Pro facilitates changes, just as in a paper storyboard, easily allowing additions, rearrangement and deletions, so this does not worry me.)

![]() |

| A section of page 1 of my script. |

![]() |

| The script for Scene 1 pasted into the Action Notes window in StoryBoard Pro. |

Using a written script may not be the best approach for everyone. Some may prefer to work from the outset with visual representations of the scenes, but I have some experience in writing fiction and live-action scripts and so it appeals to me as the right way to begin.

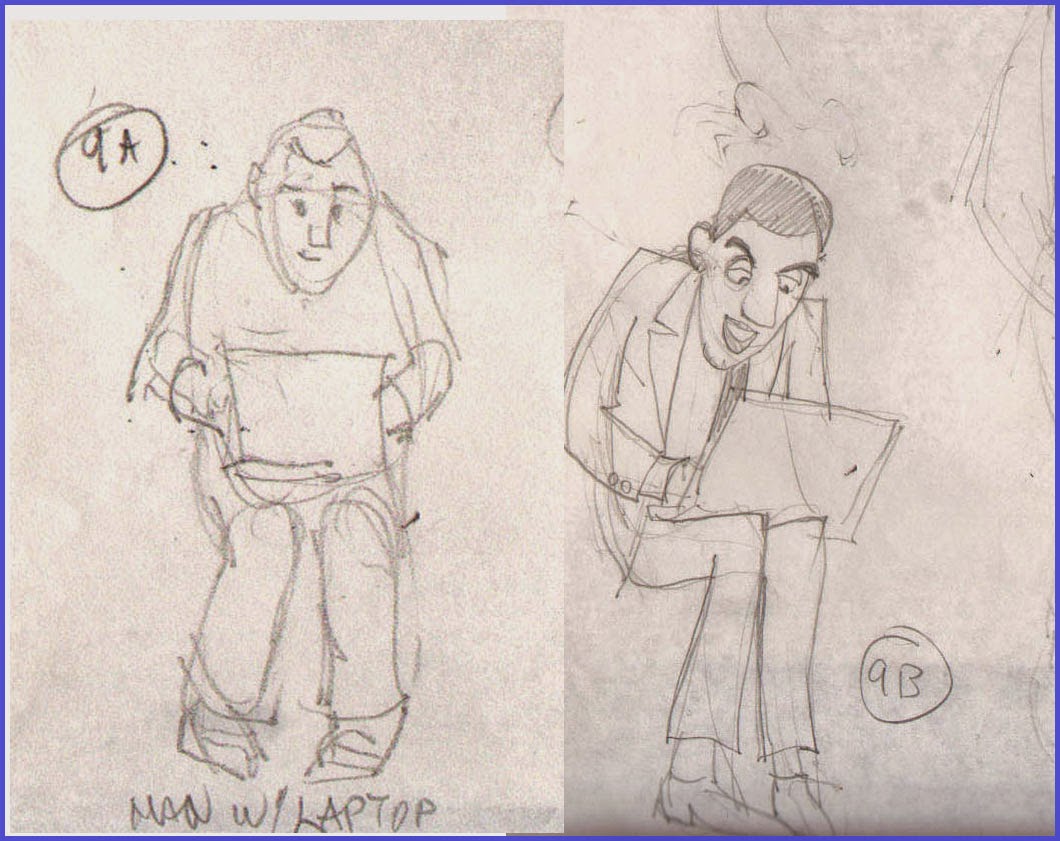

Thumbnails

Along the way I was making thumbnails on paper which I kept before me as I worked. These were just quick sketches, only a few inches or centimeters high, of poses and situations that I was visualizing as I worked through the script, and which I jotted down quickly without regard for character accuracy or precise drawing. This can be a valuable way to work, and I recommend it.

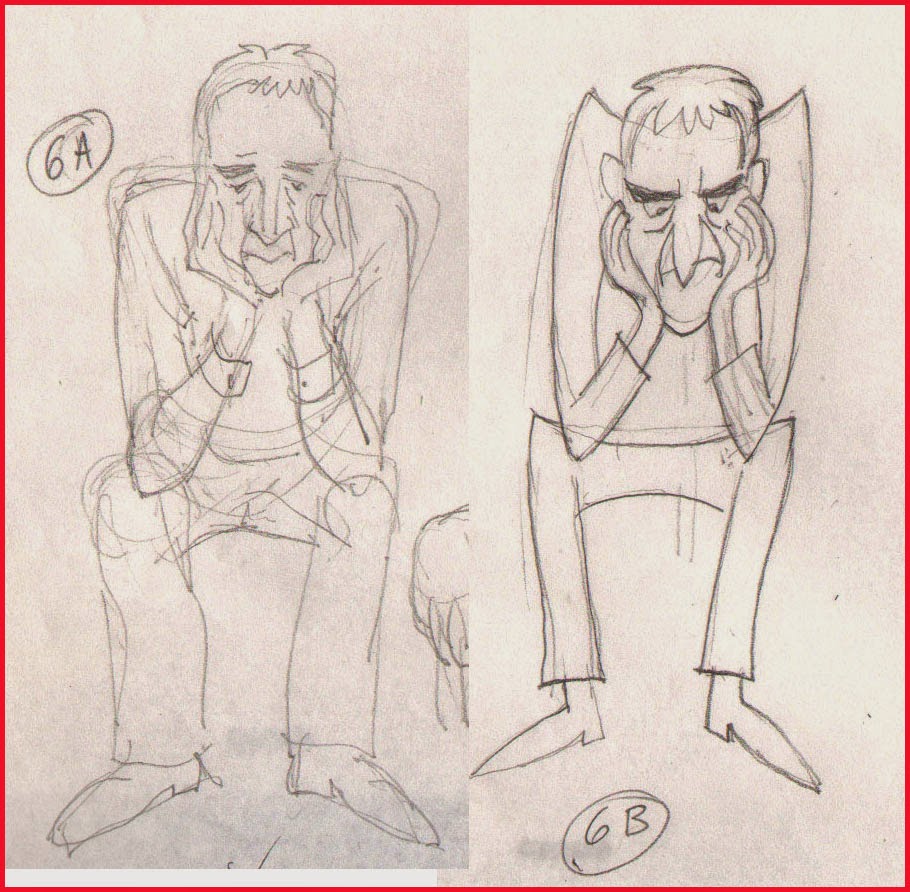

![]() |

| Early thumbnail sketches. |

Bitmap or Vector?

The StoryBoard Pro application allows drawing in either bitmap or vector modes, though not both on the same layer. The default layer choice is vector (I did not find a way to change this), and after some experimentation I found this to be preferable because of the smoothing property, a feature found in many vector drawing apps. This property may be set at any percentage from 0 to 100 and will help remove shaky or hesitant tremors in any drawn vector line. I like it set at around 20 most of the time, but this will be different for each artist. Setting the smoothing very high, however, can cause the algorithm to redraw your line without any of its original character, so this should usually be avoided.

![]() |

| Testing three settings of the Smoothness property in vector inking. |

Here I inked one rough drawing three times, using no smoothing, 50% smoothing and 100% smoothing, as indicated. If you look closely, you can see that the 0% setting gave me the most faithful rendering of the rough, yet it contains some nervous lines at the top of the cap. At the other end of the scale, the 100% setting straightened some curves completely (under the eye and at the mouth) and made very small detail almost impossible to render. Drawing a round pupil in the eye was not possible, and getting it as good as I did required 4 or 5 repeated strokes. Even the 50% version was taking too much control of the line to suit me.

Another advantage of vector inking, or course, is that the lines remain crisp at any scale.

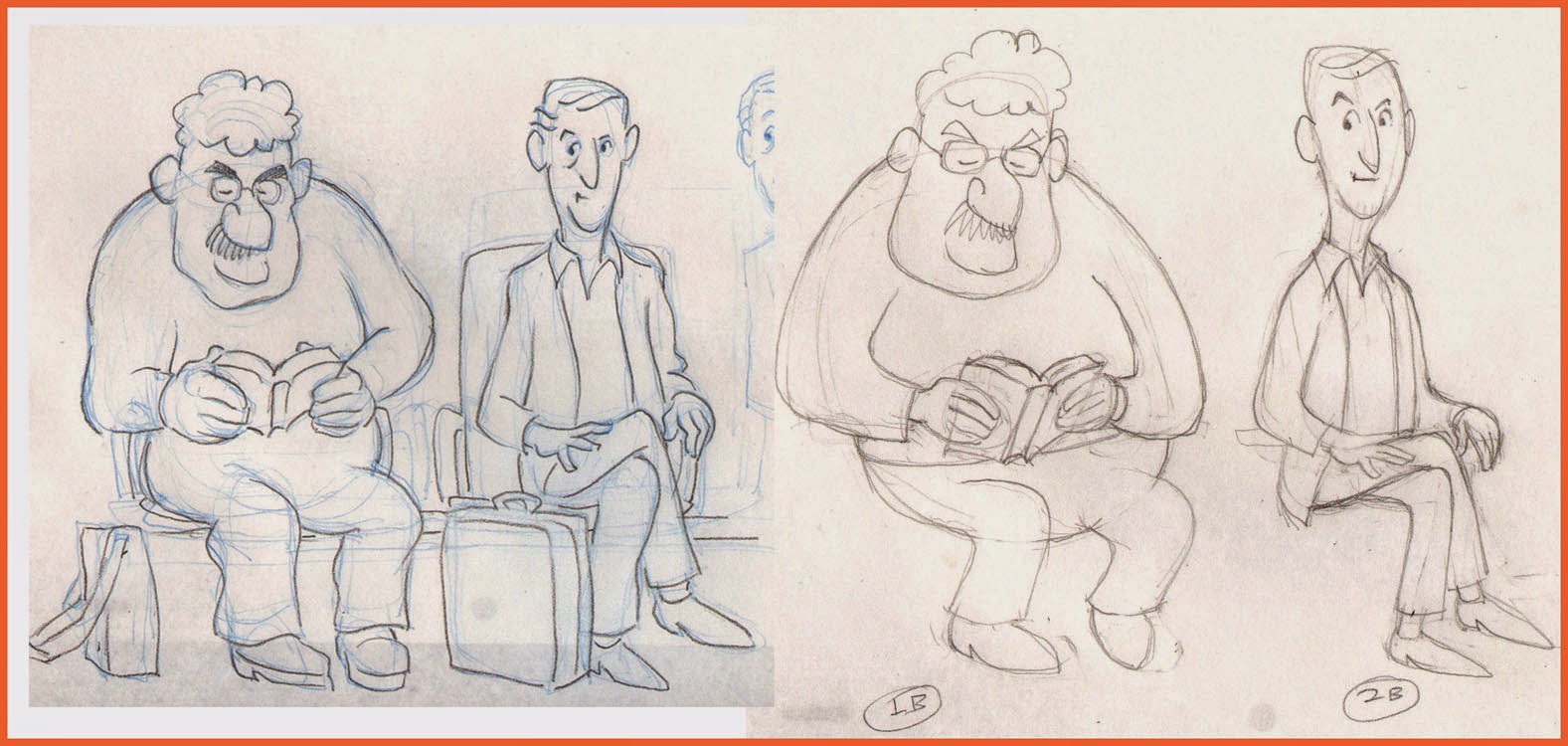

Keeping It Rough

With the idea of ending up with not just a storyboard but an animatic, I found that a good way to work was to go through the entire board in very rough form, using separate layers for whatever elements in the scene will be shown to move or change.

In the course of roughing out the storyboard, new ideas for movement, transitions or other changes will naturally present themselves. If you are working rough, it will be less painful to create the necessary layers or panels to accommodate these new things than if you were working in a more finished way.

![]() |

| Rough storyboard panel. The black rectangle is the camera field, which will be adjusted later. |

I have roughed in more than half of this storyboard as of this writing.

Next: Part 2, The Hybrid Approach